Pedagogical Opportunities and Practical Considerations for College Writing Instructors

By Dr. Stephanie Thompson

This post reflects on my challenges with the college writing and grading systems, focusing on ways to shift from traditional grading to “ungrading” methods. It discusses how grades affect students’ writing anxiety and motivation and highlights a shift towards assessment-focused approaches that encourage revision and self-evaluation.

My first college composition grade was a C+, a rude awakening for an A student. My teacher noted that the essay, while written clearly and organized in the five-paragraph theme style I mastered in high school, didn’t have enough of my own ideas. I could describe and explain, but I needed to analyze and evaluate. I resolved to improve and ultimately ended up with an A- in the class, but more importantly, I learned that I couldn’t just coast on my past successes. Grades certainly motivated me to make changes, but for many of our students, grades only activate writing anxiety.

When I began teaching composition, I decided to try out the “portfolio” method described by Clark (1993). Students would write several essays, receive suggestions for improvement and a pass/fail submission “grade,” and revise some of them for final grading. Surely students would take advantage of this opportunity and make extensive revisions? Instead, I spent the semester writing copious notes on handwritten drafts and seeing little to no changes in their revisions. The most frustrating moment occurred when a student turned in an essay on Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” that looked suspiciously like an article from The Explicator and turned out to be just that. When I showed the student the original publication, their face fell. But it was only a draft worth 5% of the final grade, he protested. Shouldn’t he just take a 0 on that and be able to write an original essay for the final grade? Ultimately, I stopped using this method. They had the chance to go to the Writing Center, schedule a conference with me, and get feedback through the peer review process. Shouldn’t that be enough?

Fast-forward to 2020, when students and faculty alike were blindsided by the Covid pandemic. My students now had to juggle work, classes, and kids at home, and my own frustrations dealing with my son’s remote learning made me empathetic to their plight. I decided to suspend late penalties on their work. So many were grateful that they didn’t have to worry about a 10%-20% late penalty that I wondered how I could further address that constant obsession with points.

After attending a virtual Association for Writing Across the Curriculum (AWAC) workshop on the “ungrading” method, I realized this method had many parallels to the portfolio approach. Ubbesen et al. (2024) described their different approaches to ungrading that varied from conferencing to a simple 0–4-point system. While their institution did require a final grade, the approach seemed to result in students feeling less stressed, more creative, and better evaluators of their own work. Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (and What to Do Instead) (Blum, 2020) describes benefits of ungrading that reflect the insights shared at the AWAC presentation. Blum speculates why faculty may be rebelling against grading: “It could be that we are concerned about the fixation on grades, which leads to cheating, corner cutting, gaming the system, and a misplaced focus on accumulating points rather than on learning” (2020, p. 3). Now, instructors have the added challenge of determining whether a student has used artificial intelligence (AI). Why grade, indeed? How can I or any other instructor in a system that requires grades apply the ungrading philosophy?

Before answering that question, I wanted to further consider pros and cons of the ungrading approach. Researchers remind us that most institutions still require grades, students need to be self-motivated to benefit from this approach, and concerns about inequity and bias persist (Hirsch, 2024; Dyer, 2024; Talbert, 2022). However, what if this approach reduces anxiety, increases motivation, and creates a more collaborative learning environment (Turcotte et al., 2023; Atwell, 2024)? Furthermore, could this approach be a way to encourage students to write in their own voices?

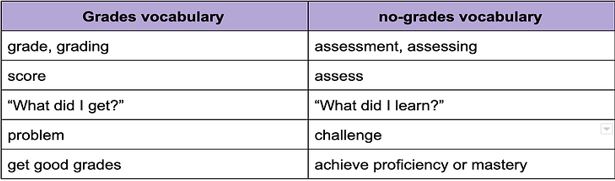

Despite the challenges, instructors can shift away from a grade-focused to an “assessment-focused” approach and encourage students to become better self-assessors. Sackstein (2021) provides a vocabulary that is a useful starting point:

Figure 1. Chart from Sackstein’s Hacking Assessment

In our modularized courses at Purdue Global where students complete an assignment aligned with a course outcome, students have multiple chances to submit and revise before receiving a final assessment; if they achieve proficiency or mastery based on the rubric, they receive an A or a B for the course. This is very much aligned with the ungrading principle.

Our traditional college composition courses also provide opportunities. In our weekly discussions, students draft parts of their assignments and share them with the instructor and classmates for advice. While discussions are graded, those points are based on whether they post, reference the course readings, and address the prompts; they do not have to meet the full criteria of the assignment itself. This gives them the opportunity to receive recommendations, make revisions, and improve their assignment grade. Last term, I tried an experiment in one of my composition sections. For their Unit 8 assignment, students who submitted by the due date would receive suggestions for improvement and have the opportunity to revise; I did not put a grade on the assignment but pointed out areas of the rubric where they could improve.

While only 4 of 25 students took me up on this offer, one who did noted their appreciation for the opportunity. All of the students who revised and resubmitted improved their grade from what the original submission would have earned, and only one student in the course submitted nothing at all. I also made sure to provide suggestions in the discussion to all who posted drafts there; again, all but one student posted a draft to the discussion board, even if it was late. Given the anxiety many typically feel about an assignment worth 15% of their grade and their fear of critique, I am hopeful that this approach could encourage more students to share their work and participate in the review process. Shifting from a “grading” to an “assessment” perspective could help our students adopt a growth mindset about their writing and focus less on the points they earn than what they learn.

References

Attwell, K. (2020, November 30). The why of ungrading. EduGals. https://edugals.com/the-why-of-ungrading-e070/

Blum, S. D. (2020). Why upgrade? Why grade? In Ungrading: Why rating students undermines learning (and what to do instead). Ed. S. D. Blum. p. 1-22. West Virginia University Press.

Clark, I. L. (1993). Portfolio grading and the writing center. Writing Center Journal, 13(2), 48-59. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1281

Dyer, J. (2024, January 8). Upgrading has an equity-related Achilles heel. Grading for Growth. https://gradingforgrowth.com/p/ungrading-has-an-equity-related-achilles

Hirsch, A. (2024, June 1). Ungrading: Decentering grades to enhance student learning. Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. https://citl.news.niu.edu/2024/06/01/ungrading-decentering-grades-to-enhance-student-learning/

Sackstein, S. (2021, April 22). Shifting the grading mindset starts with our words. Starr Sackstein: Author. https://www.mssackstein.com/post/shifting-the-grading-mindset-starts-with-our-words

Talbert, R. (2022, April 26). What I’ve learned from ungrading [Opinion]. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2022/04/27/professor-shares-benefits-and-drawbacks-ungrading-opinion

Ubbesen, M., Bruenger, A., & Lemur, B. (2024, May 3). Ungrading: Anti-abeleist and anti-racist approaches [Virtual presentation]. AWAC Virtual Workshop. https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/12wNUjPiJn8HLDzCRZdC3r9cFoNeUTA7IY2RN_UMGceE/edit#slide=id.p.

Leave a comment